* History *

The History of Harvey Cedars

by Margaret Thomas Buchholz

For questions, comments or stories about the history of Harvey Cedars write lbipooch@gmail.com

Click here for historic aerial photos.

Over the years the original Harvey who gave Harvey Cedars its name has lived in either a cave burrowed into a hummock or in a shack under a grove of cedar trees near what is now the Harvey Cedars Bible Conference. But from a 1751 deed we now know that our Harvey is as ephemeral as Harvey the Rabbit. In the deed, the locality was designated as "a hammock and clump of cedars called Harvest Quarters." And if you say "harvest cedars" often and fast enough, harvest will be clipped to harves -- and it's only a brief skip of the mouth to Harvey.

Whalers

These men who crossed the bay from bustling Colonial communities to pasture their cattle and harvest the salt hay used for cattle feed and mulch were some of the first white visitors to what is now the south end of Harvey Cedars. Whalers were the other group who used the outer beach here. As early as the mid-1600s men came north from Cape May and south from New England to pursue the abundant North Atlantic Greenland whale. They set up a lookout on the northern edge of Great Swamp, which extended from Surf City to the southern boundary of present-day Harvey Cedars. A 30-foot tower, nicknamed an "owl's tree," projected above the highest dune, giving the whaler a good vantage to spot the "right" whale, which migrated in February and March. This industry died out in the 1830s when the species had been so over-hunted a profit could no longer be made.

Until the hurricane of 1821, which made a direct hit on the New Jersey coast and destroyed the freshwater swamp with sea water, a great forest covered the south end of town on land that is now well out to sea. Stumps hacked by hand-hewn axes were observed during a blowout tide about a quarter mile offshore shortly after 1900 and again in the 1930s. Reports of earliest travelers tell of rows of huge dunes on the barrier beaches, and there is little doubt that Harvey Cedars had the same topography. The earliest town photographs show high dunes backed by a lush growth of bayberry, cedar, sumac, poison ivy and holly, then wide salt marshes stretching to the bay. (This type of dune formation still exists in a stretch of beachfront in nearby Barnegat Light.)

In 1886 the Harvey Cedars Beach Co. purchased and mapped the land from Sussex to Bergen avenues. That map shows Harvest Point extending to include Wood's Island, but it's probably not accurate, as a photograph taken just ten years later shows a walking bridge from the island to the point across a goodly expanse of water, although not as wide as today. Most of the activity in the late 19th century centered around the Lifesaving station, one of the first in the country, and the Harvey Cedars Hotel, now the Bible Conference. First opened about 1850, by 1870 the hotel was a sportsman's boarding hotel known as "Kinsey's," briefly managed by Civil War veteran John Warner Kinsey, my great-grandfather, whose family would figure in the town's history until the present day. William Sayen, from Wayne, Pa, built an expansive summer home in 1892 on the island off Harvest Point from the hotel, now called Wood's Island. His granddaughter, Katharine Wood Leonard, later remembered Harvey Cedars as a "thriving summer resort" with the hotel (at that time still separated from town by a stream), a boarding house containing the post office, Francis Fenimore's oceanfront mansion, and a large, elaborate pavilion on the ocean. (The Fenimore house was moved back from the sea twice, but both it and the pavilion washed out in the 1944 hurricane.) Vacationing children and adults alike swam, sailed, clammed and crabbed, and in the evenings had marshmallow roasts on the beach or played cards. They met the train to see who had come down or waited for the fishing boats to land to buy the makings of an inexpensive dinner.

The Borough of Harvey Cedars was formally incorporated on December 11, 1894, when a group of men living near the hotel seceded from Union Township (today's Barnegat Township on the mainland). Capt. Isaac Jennings, owner of the hotel, was named mayor. He died shortly thereafter. Jason Fenimore, who lived on the bayfront at Burlington Avenue, soon became borough clerk and his brother Francis became mayor in 1899.

Early Industry: Seaweed and Fish

Aggressive development with an eye to summer visitors and profits started in 1884, when Josiah Buzby Kinsey (son of John Warner) and Isaac Lee each bought tracts in what was called High Point (87th Street to Sussex Avenue). Kinsey owned the land to about 78th Street and centered his development around his general store on the northeast corner of 78th and the Boulevard, and a yacht club on the bayfront at 78th -- both still standing. He used his large expanse of bayfront property along Bay Terrace as a field for drying eelgrass. This seaweed was used for insulation, packing and mattresses, and was a well-developed industry in many coastal areas during the early part of the century. Kinsey's name remains in Kinsey Cove.

Lee operated another booming business at his end of town: pound fishing. Lee had operated a fish restaurant near New York's Fulton Fish Market, then became a wholesaler in Philadelphia. By 1900 he had two fish pounds in operation off High Point, two and four miles offshore. He employed 32 husky, strong men and housed them on a seasonal basis in a row of tiny cottages on 76th Street. The men topped 6 feet, 200 pounds, necessary to power the boats through the surf and haul the heavy nets, but the cottages were so small they got the nickname "petrel's nests". The two remaining petrel's nests were joined into one, which hugs the Boulevard just across from the Borough Hall. Lee paid $25,000 for the land and in 1887 built his home, still standing on the north side of what is now Lee Avenue. All of the cottages he built to rent for $50 a season on Lee Avenue have been demolished.

The train was the key to this development: Kinsey shipped tightly-packed bales of eelgrass and Lee barrels of weakfish, croakers, butterfish, flounder and bass to metropolitan markets. And the train brought the first tourists. Ed Merchant, then living in town, remembers, "We quivered in anticipation of that magic aroma that meant seashore: salt breeze, new-cut marsh hay, sun-dried eelgrass and overripe clam shells left too long in the sun. Not to everybody's taste, but for us it was the perfume of summer." In 1886, the first train into town was a one-car combination engine, passenger and freight owned by the Lee and Fenimore Train Co., painted various shades of yellow and dubbed the Yellow Jacket. By 1906 a longer summer passenger train was brought in but the schedule was erratic at best, and not a very rapid transit. Carlyle Stevens told the story, "We were coming along between Surf City and Harvey Cedars and there were no stops. My buddy and I were playing football in the empty baggage car and the ball got tossed off the train so he jumped off, picked up the ball and hopped back in. He could run faster than the train." The small, cedar shake-covered High Point station was located about where the borough hall is today. It was moved to Mallard Lane and eventually demolished. The Harvey Cedars station, little more than a covered platform, was near Atlantic Avenue.

Steady Growth in the Twenties and Thirties

As Lee and Kinsey sold off lots, and houses were built, both men dedicated several streets to the borough and in 1916, with 20 men registered to vote, Kinsey was elected mayor. Meetings were moved from the hotel to his general store. The center of activity shifted from Harvey Cedars to High Point. The separate names were commonly used well beyond when the U.S. Post Office instructed the town to drop "High Point" in the early 1930s, and remains in the name of the fire company.

About three dozen cottages had been built from Kinsey Cove to Lee Avenue and the town was a small, friendly place where everyone knew everyone else.

Construction on the Boulevard started in 1914, the year the automobile causeway was built parallel to the train trestle, and High Point grew steadily in the 1920’s. Lumber for cottages was trucked over from the mainland on the new causeway, and with a few friends, or one of Kinsey's carpenters, you could build a cottage for well under $1,000. Each house had its own well and outhouse. Electricity replaced gaslight in 1927 and in 1929 a new yacht club was built on the bay at 76th Street. Kinsey had sold the original yacht club to Dr. E. H. Smith for $850 and he converted it into a summer home for his family. This building, one of the town's first, has been restored and is in its original location next to the public dock.

Eleanor Smith (no relation), a 1920’s settler on Maiden Lane, recalled, "A huckster and butcher came from Barnegat, we'd order one week and get it the next. And we ate a lot of fish, usually we caught them ourselves. We could get all we wanted from the bay." The bay was crawling with crabs, and it was almost impossible to dig your toes into the soft sand and not hit a clam. One year a brother and sister caught so many crabs that they filled up the boat and had to swim back pulling it.

By the mid-1930s, Harvey Cedars had a hotel, a real estate office, a gas station, a general store, a tearoom (formerly Kinsey's barn), a rowboat rental place, paved roads, and a year-round population large enough to send about a dozen children off to the one-room school in Barnegat Light and to the high school in Barnegat on the mainland. In addition to the cottages in town, Frederick Small had completed his multi-home estate from ocean to bay (now Maris Stella) and wealthy Philadelphians had bought boulevard to bay tracts. Six or seven large, modern homes fronted the ocean between Sussex Avenue and the Coast Guard station on Gloucester, and driveways wound through the original vegetation to the homes built in the lee of the dunes.

The town gained a reputation as a summer art colony. Clinton and Hallie Beagary gave lessons in their bayfront home; sculptor Alexander Portnoff worked in his oceanfront home; Salvatore and Angelo Pinto, Gladys and Floyd Davis, Frederic and Sue May Gill, Helen and Earl Horter, Boris Blai and Leon Kelly all took inspiration from the sea, the light, and the solitude. Architect George Daub had built half a dozen "moderne" homes before the Second World War put a halt to building.

World War II Just Offshore

Town Experiences

Harvey Cedars experienced the war as did all coastal towns. By June 1942 the Battle of the Atlantic was being fought just offshore. German submarines prowled the Eastern Seaboard, attacking shipping, and the white, sandy beach was frosted with a thick coat of black, gummy oil from torpedoed tankers. Coast Guardsmen on horseback patrolled the beach with Doberman pinschers and German shepherds, which wore booties to protect their feet from the tar. All windows on the east side of homes were covered with black oilcloth blinds, and car headlights were painted with black eyelids for those times when the gas ration was sufficient for a nighttime drive. Blimps patrolled overhead, going back and forth to Lakehurst Naval Air Station (one crashed a few miles north of Barnegat Inlet). Navy planes flew just offshore, and once a training plane ran out of gas and landed on the beach.

By the summer of 1944 the Allies had regained control of the ocean and the beaches were again unrestricted. Beachcombing yielded an abundance of artifacts: a deflated rubber raft, life jackets stamped "USN," tins of pure water, C-rations, K-rations, and "yellow-bombs," the name the local kids gave to the three-inch, tubular sealed-glass vials containing a yellow powder that purified water. The vials made a small but satisfying explosion when thrown vigorously onto the street, leaving a white smear on the black macadam. There were larger finds as well. When the newly-installed radar on a blimp misread a whale for a submarine, depth charges were dropped and huge chunks of blubber washed onto the beach. Children used the gelatinous chunks as trampolines; my brother and I could bounce up and down without breaking into the flesh.

A Hurricane Happens

Postwar Growth

Harvey Cedars was knocked off its foundations in September 1944. A major hurricane struck with little advance warning. Severe storms had done major damage in 1929, 1933 and 1938, causing serious beach erosion, leveling dunes between 73rd and 81st streets and convincing several homeowners, including Mayor Joseph Yearly, to buy bayfront lots and move their homes away from the ocean. On September 14, 1944 they were the lucky ones. My father, Commissioner Reynold Thomas, the nephew of J.B. Kinsey and the only town official living here year-round, evacuated us and then returned to secure his dredge, which had been towed to Harvest Cove to ride out the storm. He watched the storm surge strike: "It lifted itself 25-feet above the dunes and advanced toward the boulevard in a solid wall of water, no foam. Lloyd Good's huge, oceanfront home broke in two, and the north and south wings rose up in the air like a V". Twenty percent of the houses were destroyed and many more damaged. Streets were obliterated, and debris from oceanfront homes piled up along the bayfront. Mayor Yearly directed a total resurvey of the town north of the Small estate and traveled to Washington to appeal for funds to rebuild.

Development quickened in the postwar boom years. Men who had spent their childhood summers here before going off to war returned to Harvey Cedars as permanent residents. Summer residents and renters, no longer kept away by gas rationing, returned. Families made rich by the wartime industries bought land for a second home.

The Garden State Parkway was completed in 1955, opening up the town to visitors from North Jersey. Empty lots were being filled and graded and every summer when the "old-timers" returned, they'd find a new Cape Cod or raised rancher in their neighborhood. A double row of worn, sculpturesque pilings projected from the sand parallel to the beach, remnants of jetties built in the 1920s and '30s. For bathers, a half-dozen young men guarded the beach at three locations. The 80th Street beach might be crowded with a hundred people on a big weekend. Teenagers gathered driftwood and had beach parties with blazing fires at night. All that was required was a permit from the police, issued if the wind was blowing in any direction except east.

The Barnegat Light Yacht Club, named for the lighthouse, organized an all-class handicapped sailboat race on Saturday afternoons and a Saturday evening party for families. At the south end of town, a row of small homes and some houseboats perched on the meadow along Harvest Avenue. The Coast Guard station had been decommissioned and the building was bought by the Long Beach Island Fishing Club. The old Harvey Cedars Hotel, which had stood empty for so long, became the active Bible Conference under the guidance of Rev. Al Oldham, who had come there summers when a student. His son Jonathan is the current owner. ?????

Jason Fenimore's bayfront home, with Harvey Cedars' original one-room schoolhouse next to it, was still in the Fenimore family. Paul Troast, a politician and contractor from North Jersey, bought an ocean-to-bay tract near Bergen Avenue and built two large homes for members of his family. The land surrounding Holly Avenue had been filled in by Reynold Thomas' dredging company and the street graded. Although several families whose oceanfront homes had been destroyed or damaged during the 1944 hurricane had resettled there, lots in what was then considered the "less desirable" end of town were selling less slowly than hoped. The Sayen home on Wood's Island had burned down in 1930 and the foundation, overgrown with poison ivy and bayberry, provided a picturesque view for residents and a destination point for adventurous children and teenagers. Most of the bayfront between Salem and Camden avenues remained marshland, with the exception of George Otto's small bait, tackle and boat-slip rental business. Oceanside land south of the fishing club to Troast's oceanfront home was also mostly undeveloped. The few small cottages nestled irregularly between the dunes had been destroyed in 1944.

Storm of the Century

Demolishes Harvey Cedars

In 1962 Reynold Thomas had been mayor for seven years. He had first come to High Point as a boy in 1906, and settled here in 1934. Thomas had a vision of the town that did not include extensive development. He wanted a town with a small commercial center, single family homes and no hotels or motels. (Two hotels had been built and burned down between 1900 and 1936.)

Thomas also wanted better beach protection. Three hurricanes in the 1950s had further eroded Harvey Cedars' beach, undermining several oceanfront homes. Thomas lobbied hard for state and federal beach protection. In 1961 macadam groins were constructed at intervals south of Maris Stella. Dredging sand from the bay to the ocean replenished the beach. Oceanfront homeowners guarded their fledgling dunes vigilantly, nurturing them with beach grass. It looked as though the beach, which never fully recovered from the 1944 hit, would recover. And then came the March 1962 northeaster, a powerful system of two storms which stalled over the Atlantic Ocean, which would gain the reputation as "The Storm of the Century".

Over a stretch of about 600 miles, the wind pushed the water ahead of it in long swells that rose 30 feet high in the open ocean. By the time these reached the shore they were traveling at freight train speed. As the waves reached the beaches, they mounted to the height of a three or four-story building. (Records are incomplete because the storm destroyed the recording devices on Atlantic City's Steel Pier.) This unfortunate conjunction happened close to the spring equinox and coincided with a new moon. The Jersey Shore had never seen anything like it and Harvey Cedars didn't stand a chance.

Mayor Thomas kept waiting for the wind to shift. "It always does," he said. "As soon as it backs around to the northwest, everyone starts to breath easier." Nobody in Harvey Cedars breathed easily for three days and six high tides. The high tide early Tuesday morning took out the dunes and undercut bulkheads. The high tide that night wiped out the beach. The high tide Wednesday morning floated houses off their foundations, broke roads and dug new inlets across town. The high tide Wednesday night pushed the debris into whatever structures were still standing. The high tide Thursday morning was remarked on because it wasn't quite as high as the high tide the night before. By Thursday night the storm had begun moving out, but the last high tide laid in yet more water which washed through the new inlets, one at 79th Street and the other at Bergen Avenue.

Friday morning was clear and sunny. Everything was calm and sunny. Except there were no dunes, little beach and few houses. Near Atlantic Avenue, a wave that broke gently on the strand washed westward over the level, destroyed roadbed, to the bay, with nothing to block its progress. When it was over what was left of Harvey Cedars looked like a war zone.

|

Utility poles teetered at all angles; several remaining oceanfront homes swayed precariously, spider-like, on tall piling; ripped-open houses were scattered randomly, the bay was filled with their debris. |

| All the large oceanfront homes that had survived 1944 were gone. Small's oceanfront bulkhead, considered indestructible, and two oceanfront homes were shredded. |  |

|

Masonry chimneys poked from the sand like ancient monoliths. At 79th Street a 40-foot-wide, 20-foot deep inlet divided the town. From the air the town looked like a child's Lego setup knocked askew. |

The 50-some people who had taken shelter at the Bible Conference, built on higher ground, picked their way home; some would find nothing but sand. Residents who had been evacuated by helicopter slowly returned and summer homeowners came down, all wondering if they still had a home. Harvey Cedars lost some 350 homes, 50 percent of its ratables, and won the unenviable distinction of being the most heavily-damaged town on the New Jersey coast. Many homeowners had mortgages to pay but no homes -- most insurance coverage did not include destruction by water -- and to recoup their losses residents built boxy duplexes where their homes had been. Owners of large tracts subdivided and sold off lots. Bayside meadows were filled and developed. In the 1970s sewers were installed and the Boulevard widened. Property values through the 1980s escalated beyond the wildest imagination of longtime residents. Harvey Cedars moved into the fast lane, no longer a one-track town.

Harvey Cedars 1958:

It looks like snow on the ground, but it’s either sand or gravel. That’s 76th St. on lower left, and the tiny building with the person standing on the corner is the borough hall. The house behind it was demolished for the parking lot. All the land on the bay beyond 83rd St. is still to be filled and developed. Believe it or not, with such an empty bay, this is a summer photo; three kids are fishing from the public dock on 78th St., and I am sure as I was in the plane when the photo was taken…Howard Baum’s Esso station was a decade old. Harvey Cedars tavern is on the corner of 80th St. and Nooneys on 81St. It’s hard to believe the County got 4 lanes on the narrow throughway. The 4-year old Loveladies Harbor development is barely visible at the top.

.jpg)

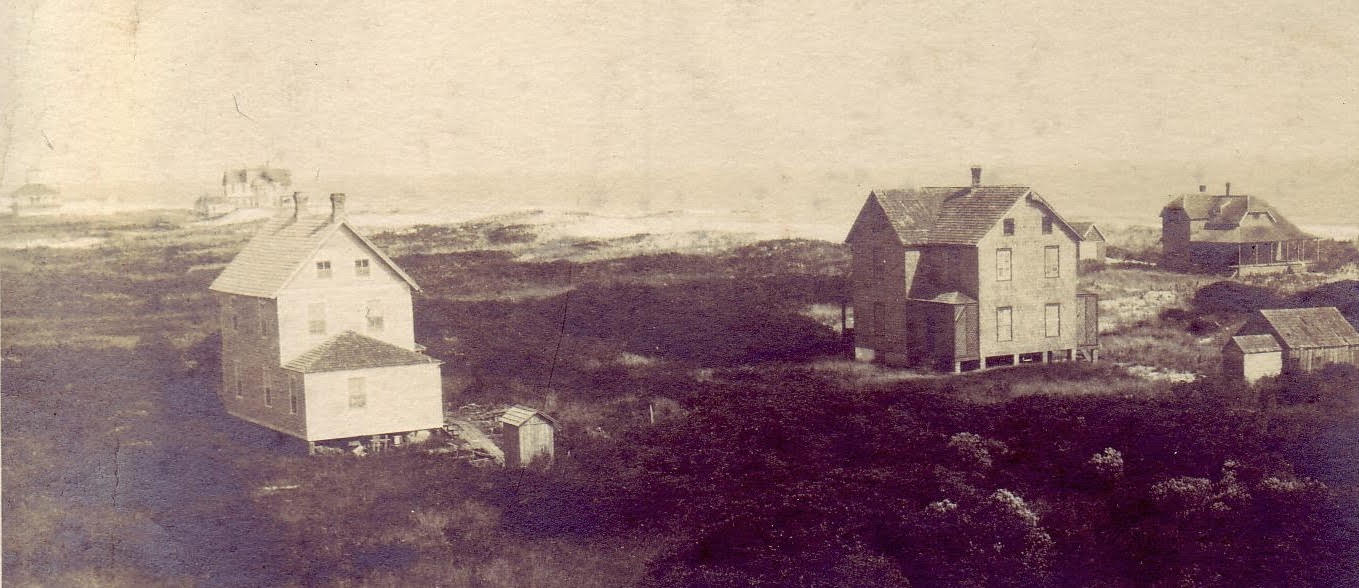

Harvey Cedars 1902:

This was taken from the tower of the then new Coast Guard Station, now the Fishing Club. Far to the left is the Pavilion built by Jason Fenimore, whose house in to the right, very close to water, was near what is now Atlantic Ave. It was moved back once and destroyed in 1944 hurricane. The little cottage on the left has a cozy outhouse in the front and the large home to its right was knocked off its foundation in the '44 hurricane. To learn what happened to it, watch this page next week.

FEELING TOO HOT?

Here is the view from Dutcher’s Boat Yard on Bay Terrace, looking east on 83rd St., taken about 1950, give or take a few years. The bay has frozen over — it used to do that often — and the freeze extends into Kinsey Creek and Cove. The large white house facing the creek with the lot on the street belonged to the Hirsch family. It was eventually demolished and there are three houses there now. Houghton’s rowboat rentals owned all the land where the little beach is. It’s where John and Bobbie Sparks’ home is now. Houghton’s Clam Bar was across the street.

1898 WOOD'S ISLAND:

If you've been in Sunset Park you might have glanced out over the water and noticed a row of pilings, usually with boats moored around it. That used to be an island connected to the land near the HC Bible Conference by a long wooden walk-way. It was called both The Philadelphia Club and the Harvey Cedars Outing Club, owned by Henry Sayen, who invited his political buddies down for some time out. We don't know who these guests are, but we can note that only the children and men wore bathing suits. The women had to cover themselves with hot taffeta dresses.

BELOW in 1910, Alice Vosseller - yes, Lloyd's great aunt - is at the helm of her sailboat with a group of friends towing a sneakbox. You can see how far the island extended to the north.

1948: Looking north from the end of 84th St., now Vosseller’s Way. It was named for both Jack and Elsie Vosseller and son Lloyd, longtime, hard-working borough employees (Lloyd’s mom was tax collector). Walk down there today and you’ll see lots of large homes in Loveladies; no more bay meadows. The bay-front house in the distance was owned for decades by Joe Wood.

MARCH 1962: Why do these town residents have such big smiles, sitting in the back of a friend’s FC 170 Jeep truck on 80th St.? Because they

still have their homes on the bayside around Kinsey Cove. If they had lived on the ocean side of town, below, they would be very very unhappy .

In the 3-day March ’62 northeaster, one-third of Harvey Cedars’ homes were destroyed. (Left to right: Anne and Phil Muhlenberg Peggy Krug, Matt and

Annette Rue and Betty Collier.)

1952:

This shot, looking north over Harvest Cove, was taken from the Coast Guard tower 50 years after the one you saw on this page last week. The Bible Conference with the white chapel to the left is roughly in the center. The house shown in the 1902 photo was moved over to Holly Ave. after the ’44 hurricane and is still there today, far left. All the land along the east side of cove was undeveloped meadowland. The town preserved the bulk of it after the ’62 storm and it's now Sunset Park.